I understand that creating a village planning and zoning function is a major impetus for incorporation. What land use powers would Edgemont obtain as a village? Currently, the Town of Greenburgh administers zoning and planning to the entire 45,000-resident unincorporated area (including the hamlet of Edgemont) through the town-wide elected Town Board and its appointed Planning Board and Zoning Board of Appeals. As a village, Edgemont itself would be responsible for those functions.

As a village, Edgemont could dedicate resources towards rezoning and marketing Central Avenue, our main thoroughfare.

If Edgemont incorporates, existing Town zoning regulations would remain in full force and effect until Edgemont elects its own governing body. At that time, if our mayor and board of trustees believe that adopting an Edgemont zoning code is in the best interests of Edgemont residents, they may do so.

An Edgemont Village zoning code would be subject to the same federal and state laws that regulate the conduct of all municipalities in New York. For example, it is unlawful to enact zoning regulations that discriminate against people on the basis of race, gender, sexual orientation, age, and families with pre-K and school-age children; also, it is not permissible to exclude groups of people from obtaining housing by, for example, making changes to the zoning code to bar any construction of multi-family housing.

The EIC believes that a village-focused comprehensive land use plan would result in better outcomes and improve Edgemont’s quality of life.

Could Edgemont Village develop its own comprehensive land use plan? Yes. With the resources and legal authority afforded by incorporation, the Village of Edgemont could develop its own community-focused plan, just as other Greenburgh villages have done over the past decades. For example, the plan for the Village of Hastings states as its main goal: “…to protect those assets which make the Village such a desirable community to live in while planning for and responding to potential impacts to its community character. It provides a positive vision for a sustainable community that balances financial realities, potential development, quality of life issues and much more. It captures our aspirations for what we can be while holding on to what we treasure.”

Why does the EIC wish to transfer zoning and planning responsibilities (and associated risks) from the Town of Greenburgh to the Village of Edgemont? We believe the Town of Greenburgh has been a poor steward of Edgemont’s land. For example, the Town has left plans for Central Avenue in Edgemont virtually unchanged from the 1970s, leading to vacancies, derelict and dangerous conditions, and a dwindling tax base with minimal action by the Town.

Discriminatory and negligent zoning actions by the Town have led to multiple lawsuits and expensive settlements for all unincorporated area taxpayers, including Edgemont residents (see below).

Further, over the past nearly fifty years, no park space has been created by the Town within Edgemont despite multiple opportunities.

We believe an incorporated Village of Edgemont would enforce its own codes and dedicate resources to developing abandoned properties and expanding our commercial tax base.

We believe zoning and planning would be improved in Edgemont if it were administered by people who live here and are accountable directly to the community. Currently, Edgemont represents only 8% of the Town-wide vote, so we have limited ability to influence important quality-of-life matters such as planning and zoning.

The Town has suggested that Edgemont could obtain zoning powers without incorporating. Is that possible? No. In New York, control over zoning and land use is dictated by law by state law. Incorporated villages are required to maintain legislative and administrative control over land use within their borders, while towns are likewise responsible for their unincorporated areas. Villages and towns are legal entities which can sue and be sued and thus be held accountable legally for the consequences of their decisions.

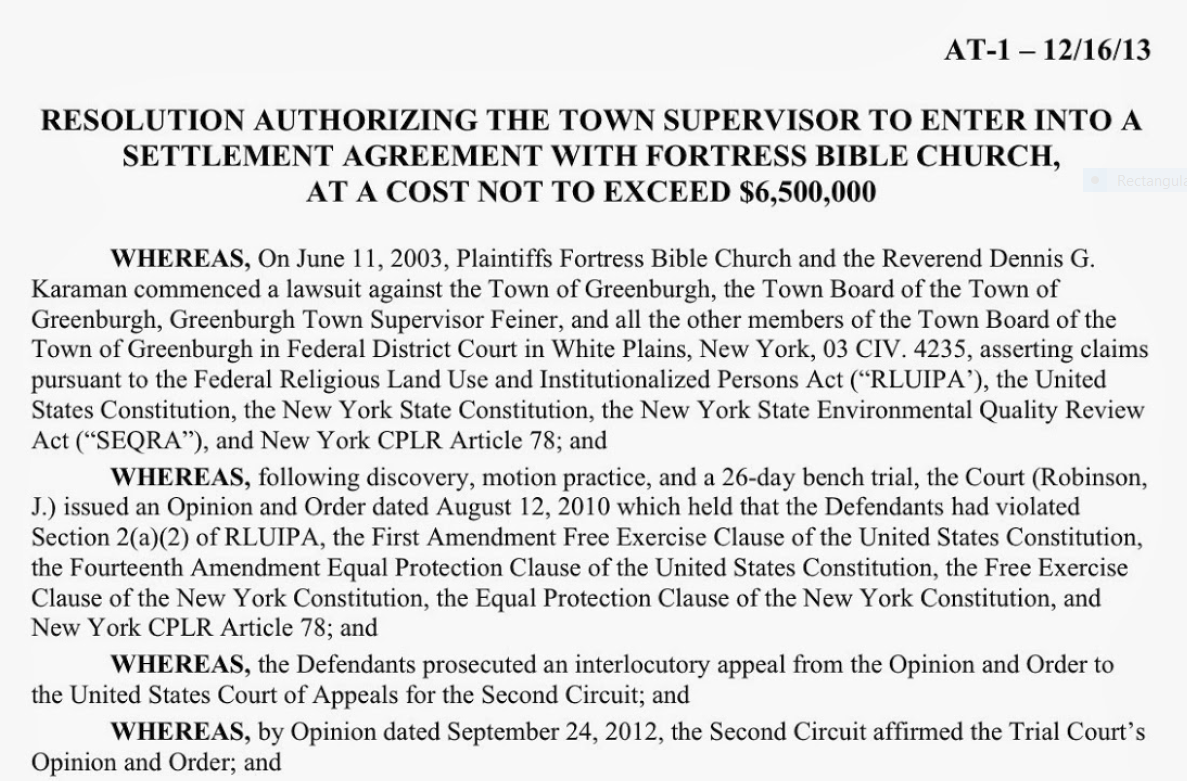

What are some examples of poor land use management by the Town of Greenburgh? Unincorporated area taxpayers are still paying off a 2013 settlement in the amount of $6.5 million for the Town’s violation of the First Amendment rights of the Fortress Bible Church, a Mount Vernon-based congregation that sought to build a new church on Dobbs Ferry Road. At the time, that was the largest religious discrimination settlement by a municipality ever in the United States.

At the Fortress Bible trial, a federal district judge found Town Supervisor Paul Feiner’s testimony “not credible” and was “troubled by his refusal to answer a simple question.” On appeal, the Second Circuit affirmed the trial court’s findings that “Town staff, including at least one Board member, had intentionally destroyed discoverable evidence,” that “the Town was acting in bad faith and in hostility to the project,” that the Town “attempted to extort from the Church a payment in lieu of taxes,” that the reasons the Town offered for its actions “were not sincere,” and that the Town was “motivated solely by hostility toward the Church.”

The unincorporated area of Greenburgh (not the villages) funded debt service on the Fortress Bible bond issue, which matured on April 15, 2024 after millions in dollars of payments.

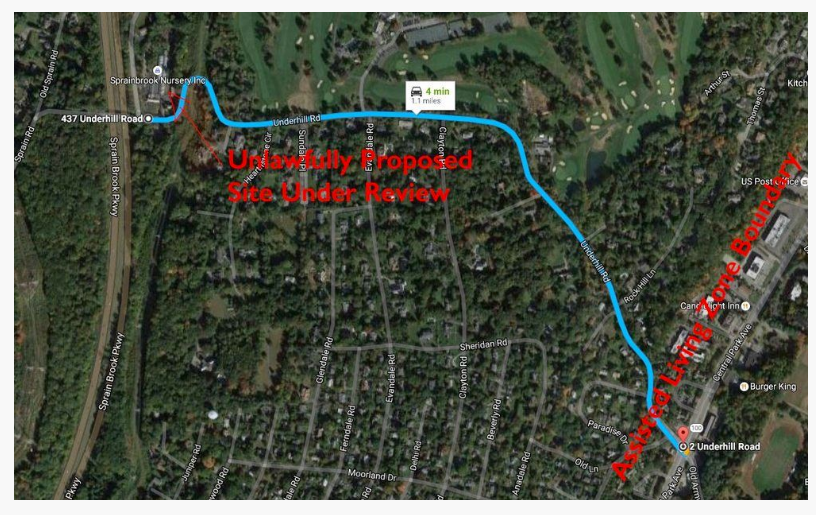

In the Shelbourne assisted living project, the developer had for years sought to build an assisted living facility in Edgemont at the site of the former Sprain Brook Nursery. The Greenville Fire District (GFD), Edgemont’s local fire department and EMS provider, raised concerns that the Town had ignored potential safety impacts to GFD staff. Specifically, the new facility would require more than 100 medical emergency trips per year by the GFD’s EMS workers along a steep, windy and dangerous portion of Underhill Road.

The GFD and some residents also complained that, in approving the project, the Town ignored a key provision of its zoning code that requires assisted living facilities to be situated within 200 feet of the closest state or county road. The law further requires that the route from the facility to the nearest such state or county road (in this case, Central Avenue) must be direct and non-circuitous.

In approving the Shelbourne project variance, the Town of Greenburgh blatantly ignored its own zoning laws, which were enacted to protect the safety and welfare of residents of the unincorporated area.

Nonetheless, the Greenburgh Zoning Board of Appeals granted Formation-Shelbourne an unheard-of 3,000 percent variance to overcome the 200 foot distance requirement—allowing Formation-Shelbourne to construct its 60,000 square foot facility in a residential neighborhood, over a full mile from Central Avenue.

In fact, the planned facility could not possibly be located in Edgemont any farther from where the law normally allows such facilities, as explained by one Edgemont resident to the Town Board.

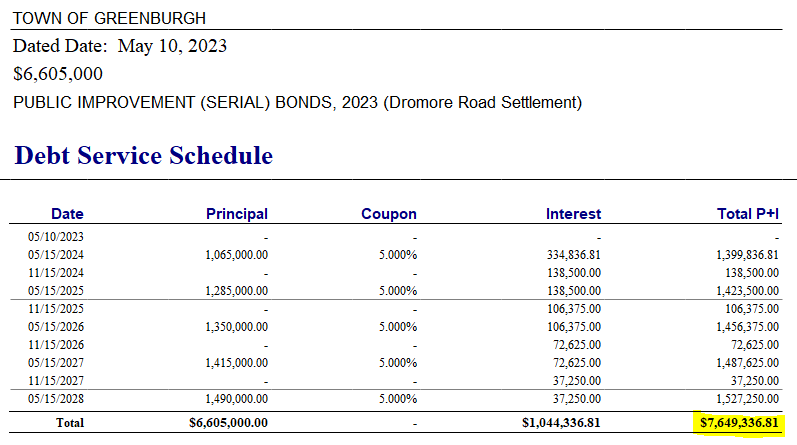

In 2021, the Town Board approved a $9.5 million settlement of a lawsuit brought by the would-be developer of the Dromore Road property in Edgemont. Only $2.75 million of that is covered by insurance—leaving some $6.75 million (plus interest), and over $4 million of legal fees already expended, on the backs of unincorporated area taxpayers.

The problem began in 1997 when the Town prepared a faulty zoning map, which mistakenly reclassified two acres of property on Dromore Road that were zoned for single family homes as being in the Central Avenue mixed use zone. The Town then failed to correct the error year after year, even when a would-be developer, aware of the Town’s mistake, met with Town officials to notify them of its intention to build multifamily housing on those two acres (where, in fact, such a project would not have been permitted but for the Town’s mistake).

Even though it had ample opportunity to do so for nearly ten years, the Town did not seek to correct its error until after the developer filed its plans with the Town in February 2007—but by then it was too late. The Town’s blunder led to years of litigation in which the would-be developer first sued the Town in state court and then, having succeeded there, brought suit in federal court claiming interference in violation of the Fair Housing Act.

The Town paid for the settlement and associated expenses through reserves and a 2023 bond issue, which again will be covered only by unincorporated area taxpayers. Our payments run through 2028 as shown below.

Is there a transition period for zoning and planning ? Yes. Under Village Law 2-250, all town zoning laws remain in effect in newly incorporated villages for two years, unless and until the newly elected village board chooses to enact its own zoning laws to replace the Town’s zoning laws. Section 250, which contains the two-year provision, states that: “…any such local law, ordinance, rule or regulation shall cease to be in effect in the village or any part thereof when so determined by any general, special or local law, or when replaced replaced by any general or special law covering the same subject matter; and provided further, however, from the date of incorporation the village may prepare and enact local laws, resolutions, rules, and regulations to be effective as provided in such local laws, resolution, rules and regulations.”